Dear Readers, today, I would like to invite you to Kenojuak Ashevak’s world.

Directly from my struggling heart to yours…

I long gave up keeping it together yet still we must find ways to keep it moving and transforming even in the most horrendous times.

I have been oscillating between writing and non-writing, being and non-being. There are about four newsletters I have begun and abandoned. Not the right time. I keep hesitating to write and share in the open. Am I distracting others? Well, even though I don’t write there are a ton of distractions and they tend to purely distract, so that is not a good reason. Yet, some days, it’s just complicated to survive in the Global South and be a part of disadvantaged ones, while trying to metabolise the human world through written word and art. Nobody around me did or does, that was my hint… You don’t have much say when the mystery pulls your hand and your tail. One thing I know and I wish to be more vocal about is how the garbage and the intensity Global North1 is generously generating, needs to be acknowledged and distributed amongst our human community. It’s just too exhausting to see how little many artists and writers from that side of the world, with attention, means and following even care.

In the midst of my oscillations and fossilisations…

On the full moon, someone came into my home from the Arctic, held my hand, and filled my heart with her story and her art.

Since I was a little kid, I had a fascination about ice, snow, igloos, north, darkness, stars and Inuit, so having an Arctic creativity orbiting with me is a dream come true. I am writing this as I am simultaneously exploring her work and life. Her art is such a celebration during these times of damnation… I had to share this with you, without waiting.

Kenojuak Ashevak (1927-2013)2 is an Inuk artist who evokes planetary joy and wild soul connection in a way only an indigenous person can and shall in me, and perhaps in us all. Do join me in discovering and celebrating the life and art of the grandmother of Inuit art, Kenojuak Ashevak with curiosity, reverence and respect.

Please note that this newsletter is too big to fit your mailboxes because it contains plenty of art. You can keep on reading it on the Substack website. At the end of the article, there are also resources and an Oscar-nominated short movie about the artist.

An Igloo Born Artist, ᕿᓐᓄᐊᔪᐊᖅ ᐋᓯᕙᒃ

Kenojuak Ashevak was born in an igloo3 on Baffin Island in 1927. She grew up on the land, living in seal skin tents and moving from camp to camp following the migration of food sources. Her father was a hunter, fur trader and respected angakkuq, a shaman, a medicine man. Upon coming into conflict with Christian converts, he was killed when Kenojuak was six.

At an early age, she learned how to hunt, sew, repair seal skins for trade and move with the rhythm of the land and sea. When she was 19, she was arranged to marry a local hunter, to whom she would throw pebbles at when he would approach her. In time, however, she came to love him for his kindness and gentleness. Together, they also collaborated on artworks. After Johnniebo Ashevak’s death, she got married twice more and got widowed after her husbands’ death. She had eleven children, seven of her children died in childhood and she adopted five more children.

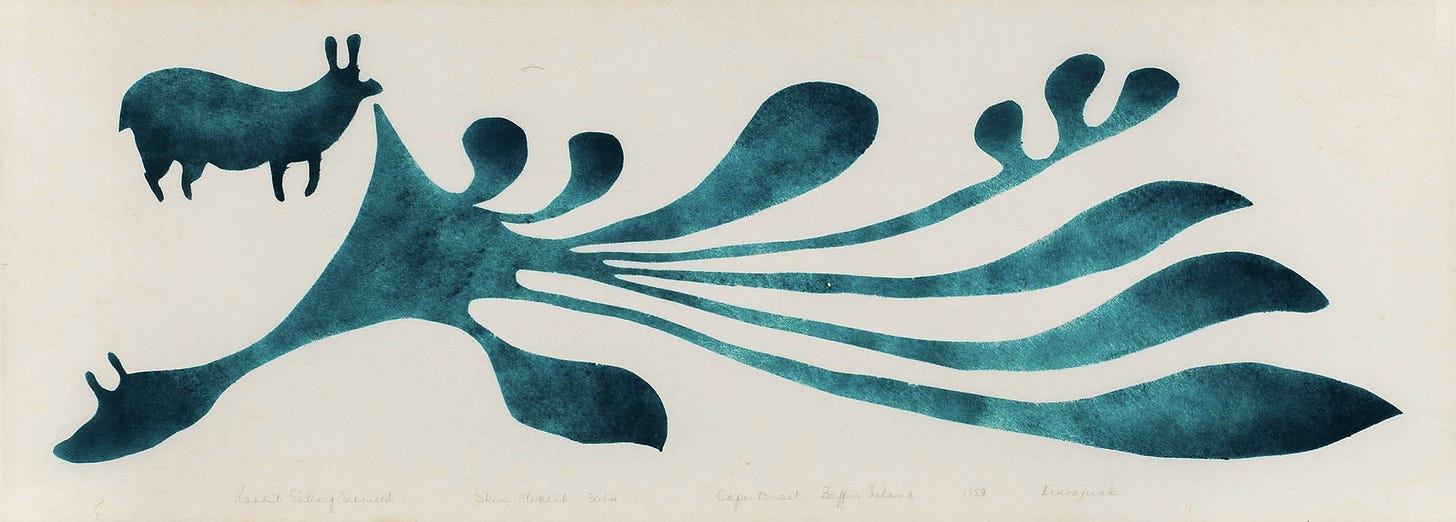

When she was twenty-five, Ashevak got tuberculosis and had to stay in a Quebec hospital for three years away from her family. There, she began practicing art and various crafts like toy making as a pastime. Later, while visiting Cape Dorset, she met an artist and civil servant, James Houston and his wife Alma Houston4 who were establishing an arts program there and they encouraged her to pursue graphic arts. Kenojuak Ashevak was the first woman to join.

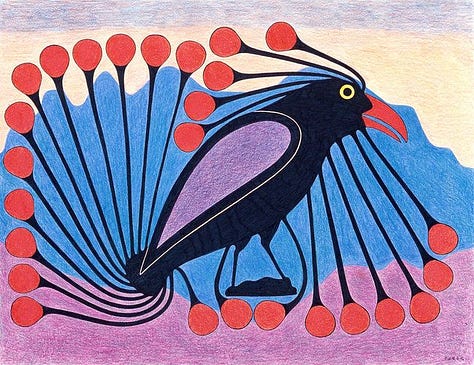

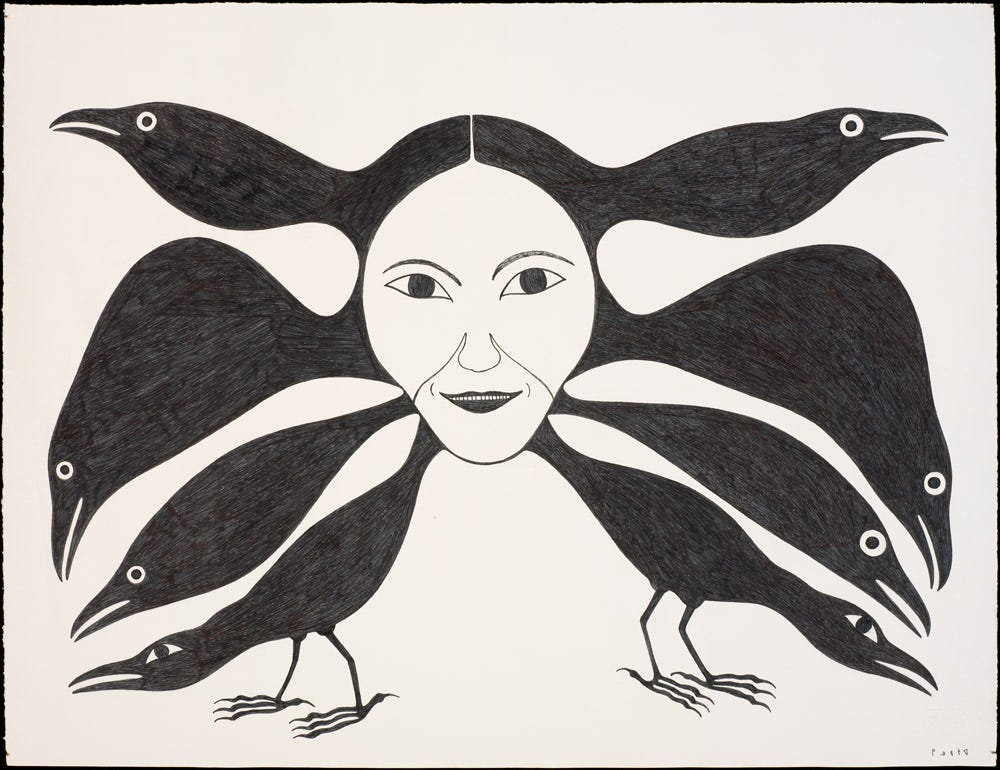

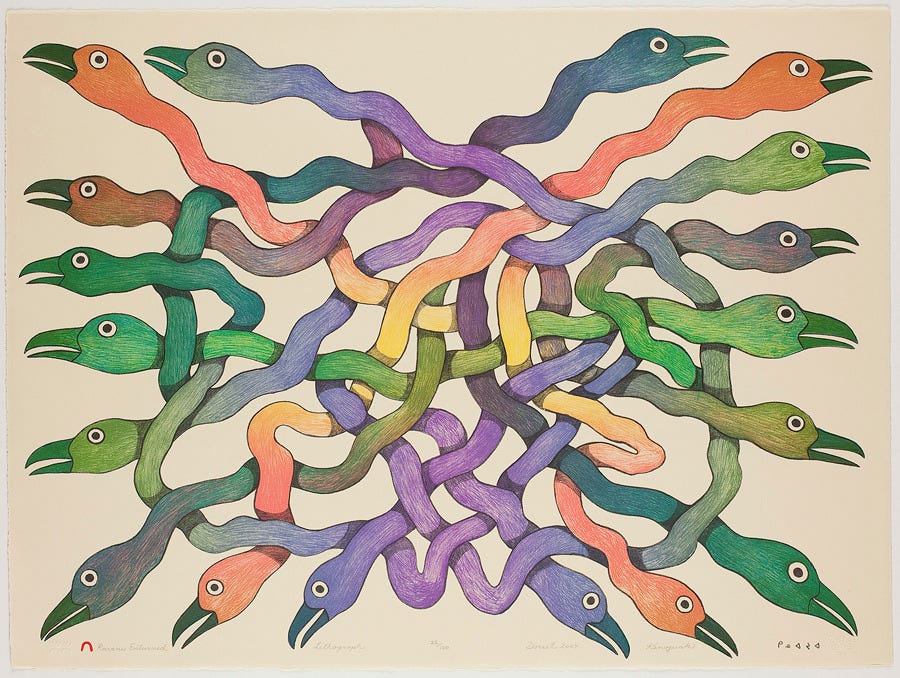

She began drawing in the late 1950s and, up until her death, had a continuing appetite for experimenting with new techniques. During the last months of her life, Kenojuak produced a series of four-by-six-foot (121x180cm) drawings from her bed and she died from lung cancer in 2013 in Kinngait, Canada.

Thanks to her art, she could support her children, her grandchildren, her great-grandchildren and her community.

“When I first started to make a few lines on paper, my love, Johnniebo, smiled at me and said ‘Inumn,’ Which means ‘I love you.’ I just knew inside his heart that he almost cried knowing that I was trying my best to say something on a piece of paper that would bring food to the family. I guess I was thinking of the animals and the beautiful flowers that covered our beautiful, untouched land” Kenojuak Ashevak, 2008

Kenojuak Ashevak understood some English, particularly later in life, yet it seems she preferred to express herself in her native language Inuktitut which is currently spoken by around thirty-five thousand people.

“There is no word for art. We say it is to transfer something from the real to the unreal.” Kenojuak Ashevak

In an interview when Ashevak was asked what makes her images so appealing to collectors, to galleries from all around the world, she stated that when she made a drawing she started with something and concentrated on it very hard. She did her best to depict whatever comes from her mind and imagination.

In 1964, a New-Zealand born filmmaker, John Feeney made a documentary about her named Eskimo Artist: Kenojuak5 and it was nominated for a short documentary Oscar and earned BAFTA award for best short film that year. In the film, they show how her original drawings were first transferred to stone then a craftsman chiselled the surface away from the design. And finally, to create the prints, the ink was applied to the cut stone and the paper was pressed against stone surface. (I added a link to the documentary film down below.)

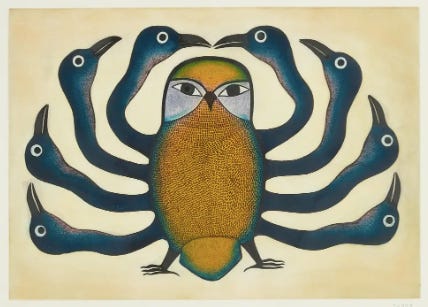

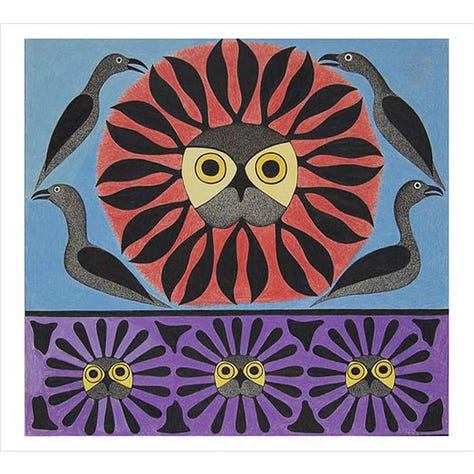

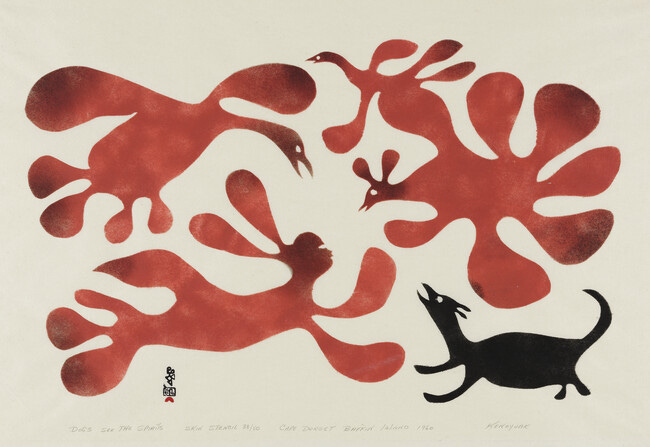

Ashevak was considered ‘the bird artist’ of Cape Dorset. She drew plenty of birds, especially owls throughout her life. The owls were Ashevak’s favourite drawing partners. The Enchanted Owl (the first artwork on the top of the article) is crowned as her most iconic and widely reproduced piece. It was selected for a Canada post stamp in 1970 and is a symbol of Canadian art.

Letting her hand be guided by her intuition and her owl being, she depicted the owls in more than one hundred prints.

“Arguably the most widely recognized Inuit artist in the world, the many achievements of Kenojuak Ashevak have cemented her status as a leading figure in the history of Inuit art. One of the first women to participate in the Kinngait (Cape Dorset), NU, printmaking program, Ashevak's graphic works immediately gained attention for their harmonious compositions and captivating depictions of Arctic wildlife.

In 1970, her iconic print The Enchanted Owl (1960) became the first artwork by an Inuk artist to appear on a stamp, helping to introduce many people to the world of Inuit art.” Inuit Art Foundation

“I think the climate is changing rapidly. When I was young we didn’t have climate change. The climate change I’ve seen is the ice is melting rapidly in the springtime. In the late fall the ice used to come but these days it doesn’t until December.”

Kenojuak Ashevak (1927-2013)

“My mom’s work makes you feel as though you are in a dream. She drew from her imagination.” Silaqqi Ashevak, Kenojuak Ashevak’s daughter6

Did you know Kenojuak Ashevak and her art before?

I did not until a few days ago… well, the Moon has their magical ways and rays to connect creativities and entangle imaginations further. I am very grateful for this wonderful symbiosis. How do you feel about her art and her world?

“I am an owl and I am a happy owl. I like to make people happy and everything happy. I am the light of happiness and I am a dancing happy owl.”

Kenojuak Ashevak

Thank you, Grandmother Kenojuak. Enchanted to meet you.

Nakurmiik Kenojuak Ashevak, ᓇᑯᕐᒦᒃ ᕿᓐᓄᐊᔪᐊᖅ ᐋᓯᕙᒃ 7

May her story, her joy, her resilience, her creativity and her connection to the land be an inspiration for us all. She kept on creating, and moving so must we.

Gizem Gizegen, 2025 Istanbul, ☉ Gemini ☽ Aquarius

Resources:

Oscar-Nominated Short Film: Eskimo Artist: Kenojuak

In conversation with Ashevak’s daughter Silaqqi Ashevak

30 Ways To Describe An Owl According to Kenojuak Ashevak

The History Behind Nonavut, Our Land

Although I often stay away from dividing things, these are the realities of our systems… So I wish to invite Global South and Global North more into conversation.

She was just three years older than my own maternal grandmother who passed away in 2008.

In some places it was said that she was born in an igloo, in some others just in a camp. My imagination favours igloo… yours might also.

“She was hesitant at first, claiming that she could not draw and that drawing was a man’s business. Yet the next time that she visited the Houstons, the sheets of paper that Alma [James Houston’s wife] had given her were filled with pencil sketches” – James Houston, 1999

The film is 19 minutes long and you can watch it on Youtube. Also, it came to my knowledge that the word “Eskimo” is an outdated and offensive term. It was formally rejected by the Inuit Circumpolar Council in 1980 and is no longer used in Canada.

There is a short interview with Kenojuak’s daughter in the resources.

“Thank you very much Kenojuak Ashevak” in Inuktitut

Toujours un plaisir de vous lire et merci pour la découverte! Il me tarde de mettre la main sur votre livre "La Graine ".

"I am a happy owl" this touches me so much. Thanks for this healing discovering.